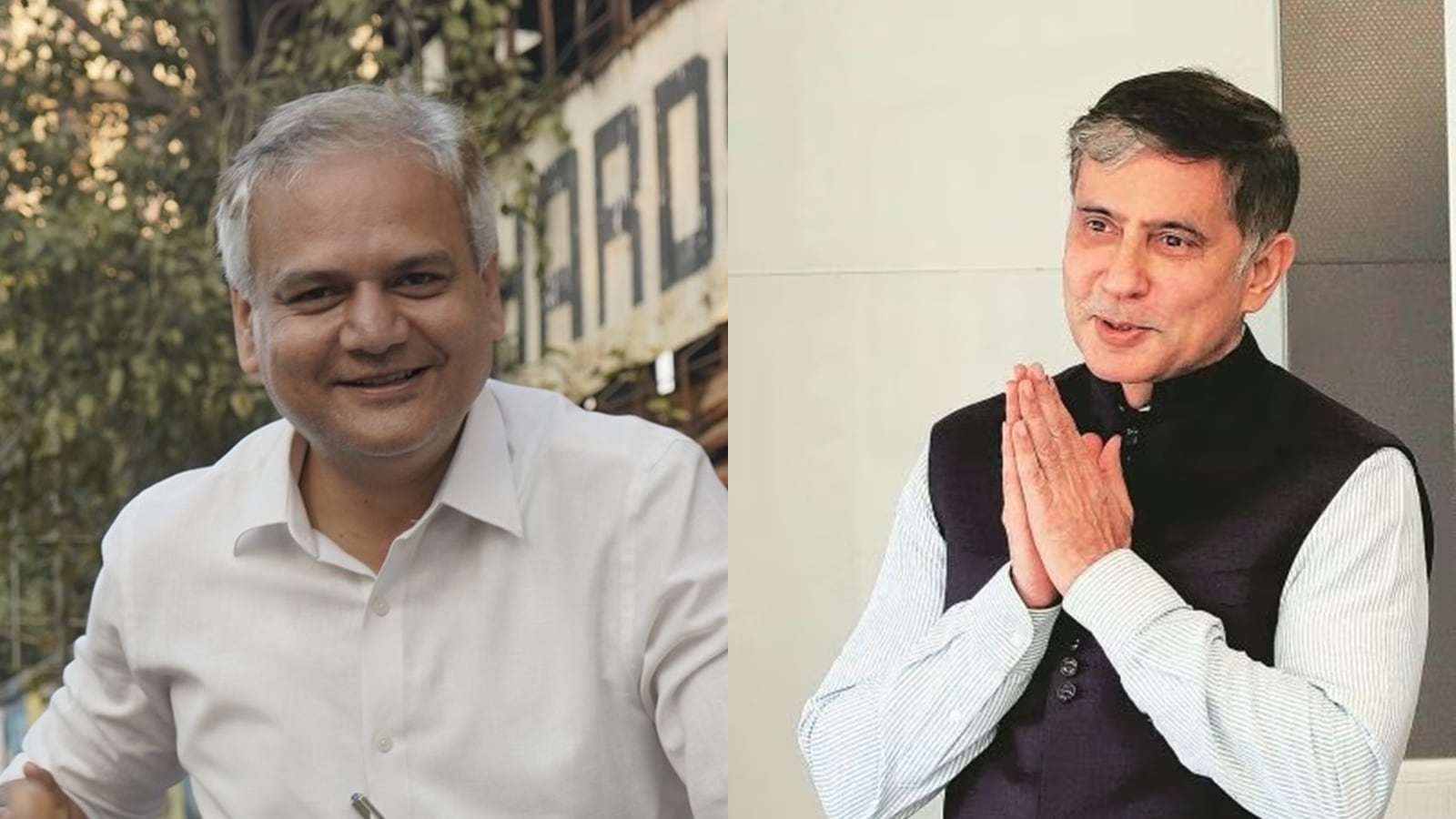

The latest political furor in Mumbai has been caused by the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) proposal to impose a congestion tax on the city. Last Sunday (February 8), newly elected municipal councilor Makarand Narwekar sent a letter to Mumbai civic chief Bhushan Gagrani, asking him to consider implementing a congestion tax in Mumbai. The move was heavily criticized by the opposition Shiv Sena (UBT), which said the proposal is being considered to “loot” Mumbai.

A congestion tax is a fee levied on vehicles entering densely populated, high-traffic areas during rush hour. The goal of this tax is to limit vehicle loading in areas that are already highly congested and regulate emissions levels, which contribute to poor air quality.

In his letter to the civic chief, Narwekar proposed a tax slab of Rs 50 to Rs 100 per entry during peak hours (8 to 11 am and 5 to 8 pm). It also suggested that high traffic areas could be demarcated using existing CCTV networks and automatic number plate recognition (ANPR) cameras at entry points.

This methodology is commonly practiced in Europe in cities such as Stockholm and London. In Asia, Singapore has this provision. However, such a tariff has not yet been implemented in India.

In the meantime, here’s a detailed look at what this tax means, what research says about its impact, and whether it will work in India.

Congestion tax: a global practice

A congestion tax was first proposed in Singapore in 1975 on streets leading to the Central Business District (CBD). Singapore’s economy expanded rapidly from the mid-1970s, leading to a rise in car ownership. According to the article “Making a case for congestion pricing in Indian towns”, written by Dr Ramnath Jha, retired IAS officer and urban mobility expert, for the Observer Research Foundation (ORF), “the CBD, which saw a five-fold increase in employment, was especially plagued by congestion. To address this situation, Singapore introduced the Area Licensing Scheme (ALS) in 1975. This was a tool primarily to control traffic volume. To begin with, ALS was a manual system of Motor vehicles entering a restricted zone had to pay a fixed fee from Monday to Saturday during peak hours (7:30 a.m. to 10:30 a.m.).

In 2003, London implemented congestion charges covering a 22 square kilometer radius of the city. According to the ORF newspaper, the charge was set at £8, applicable Monday to Friday from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. Environmentally friendly vehicles were exempt.

Story continues below this ad.

“A complex network of cameras spread across the congestion charge zone records car license plates and compares them with a register of vehicles that have paid the charge. Drivers who do not pay the congestion charge within three days are fined £160,” the paper states.

In Stockholm, a similar charge was implemented in 2006 after the Swedish Parliament approved a pilot project, even though two-thirds of the city’s population initially opposed the system.

Was the congestion tax beneficial?

One of the successful results of implementing a congestion tax was seen in Stockholm. The pilot project lasted seven months and included three separate initiatives. The first was to increase the existing public transport system, through which 197 new buses were purchased and 16 new bus lines were introduced, expanding services on existing routes. The second involved building parking lots outside the city limits so people in remote locations could leave their cars and use public transportation. The third was the imposition of a congestion charge in the city centre.

“During the pilot process, congestion was drastically reduced by between 30 and 50 percent and in the subsequent referendum, two-thirds of citizens voted in favor of the tax being made permanent. The congestion tax was then introduced permanently and in 2013, another Swedish city, Gothenburg, adopted it,” the newspaper states.

Story continues below this ad.

In London, the congestion charging zone saw a 26 per cent reduction in congestion in 2006. Other benefits included a reduction in pollution, an increase in bus transport and an increase in revenue totaling £122 million in the 2005-2006 financial year.

The income generated by congestion charges is primarily used to cover the operational costs of the scheme and the remainder contributes to the maintenance of the city’s public transport system. The scheme has been more successful in discouraging older, polluting vehicles from entering central London and has led to a sharp decline in the use of diesel cars. These results have helped improve air quality in the city, the newspaper states.

Congestion tax in India

Before the BJP’s proposal in Bombaya congestion tax was proposed to Bengaluru by the Congress-led Karnataka government in September 2025. As per the proposal, single-occupancy vehicles entering Bengaluru’s Outer Ring Road (ORR) will be charged this fee. The proposal said that the amount would be raised through FASTag and the scheme was aimed at promoting car-sharing and public transport. However, following public backlash and political criticism over poor infrastructure, Karnataka Deputy Chief Minister DK Shivakumar scrapped the proposal.

Delhi He had also proposed the implementation of said tax, but it was not implemented.

Story continues below this ad.

One of the key reasons why such a tax has not been implemented in India is the lack of alternative infrastructure support to facilitate the policy. Cities like London or Stockholm have strong public bus transport networks. Meanwhile, in Mumbai, the current fleet of BEST buses has been shrinking and its fleet size has reached an all-time low.

Although the metro has come up in Mumbai, it is not yet completely completed and the completion of this project will take at least another decade. Another major hurdle for the implementation of this tax in Mumbai is that the current Motor Vehicles Act (MVA) does not provide for such a charge.