Season 1 of Nikkhil Advani’s period drama Freedom at midnightwhich was published a couple of years ago, ends with signs of an angry nation demanding: “Gandhi must pay.” It is appropriate then that season 2 It culminates with the assassination of the Mahatma, which took place on this day 78 years ago, in 1948. But it is designed less as a price that Gandhi had to pay, and more as a minor sacrifice that he had to make for the greater interest of a divided nation. The most violent excess toward a symbol of nonviolence is not a victory of hinsa as much as a plea for peace.

Gandhi is assassinated five months after the independence and partition of India. It is a phase of extremes: the joy of liberation from more than 200 years of colonial rule, along with the irrevocable anguish that comes with a nation divided along religious lines. This is no ordinary territorial bifurcation, but large-scale unrest and displacement in the eastern and western corners of India.

In his seminal 1981 novel, Midnight’s Children, Salman Rushdie chronicles that turbulent time in the chapter ‘Snakes and Ladders’ as a macro equivalent of the board game: the ladder of Independence and the snakebite of Partition, the descent rocked by the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi and the gradual rise of a nation unwilling to let that sacrifice be in vain.

Furthermore, in that novel, the protagonist Saleem remembers learning about Gandhi’s assassination during a film screening, prompting his family to rush back and seek refuge at home, under the assumption that a Muslim killed the Father of the Nation. The escapist fantasy of a movie is hijacked by the harsh truths of reality. So to speak, the killer was not a Muslim, but does that matter?

Would history take a different turn if Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated by a Muslim? Season 1 ends with a hint of that alternate reality, but Season 2 explains how Gandhi makes sure that even if his assassination is inevitable, he must make it worth it. Probably having foreseen and accepted his impending end, Gandhi continues almost to death, once to urge all rioters to lay down their arms and then to ensure that the terms of partition are fairly carried out not only by Pakistan, but also by the Indian government.

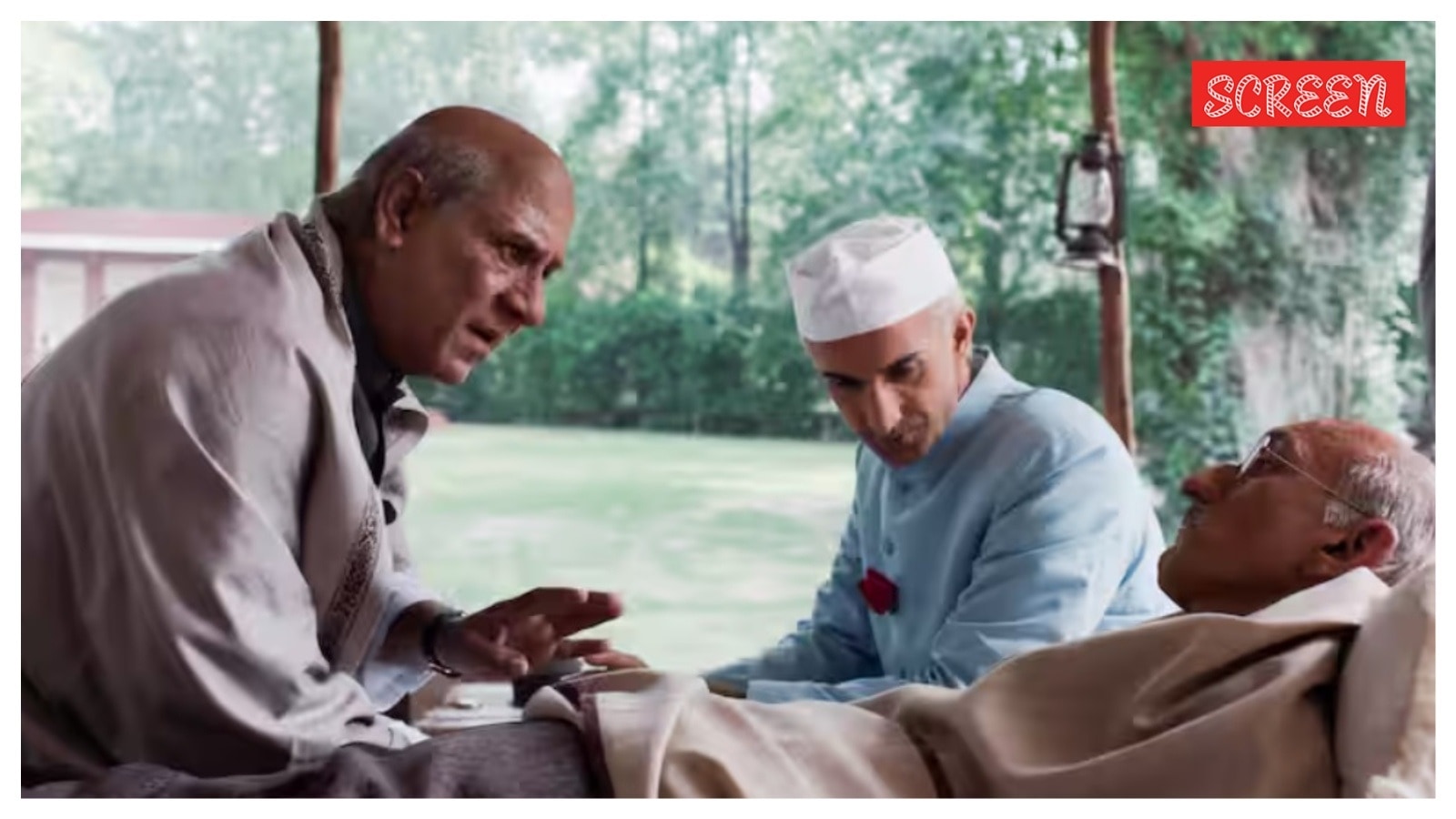

By supposedly turning against those perceived as “his”, be they Congress members like Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Home Minister Vallabhbhai Patel, as well as his fellow Hindus, Gandhi takes a firm stance against communal riots. Their allegiance lies not in any religion or in any half of the country, but in a broader moral code that governs a country divided by politics. If he is the Father of the Nation, he is not the Father of Naya Bharat, but of a once-India, stretching far beyond the Radcliffe Line.

“Do not discriminate pain between ours and theirs. Shed as many tears over the pain and loss of others as you do over your own,” Gandhi’s advice to a despondent rioter in Calcutta was not just a symbolic pearl of wisdom, but his way of life. He made peace in Pakistan as important a part of his mission as harmony in India. Unfortunately, he was killed before he could fulfill his last wish of going to Pakistan. Was it an attempt to stop the Mahatma from spreading peace in Pakistan as he did in India? Or was it an act of revenge towards the man who cost India the sum promised to Pakistan?

Story continues below this ad.

The way that episode progresses, Nikkhil Advani emphasizes that the religious or nationalist identity of the murderer does not matter as much as his existential identity. More than the man who assassinated Gandhi, the show follows the journey of his assassination attempt: Madan Lal Pahwa. Pahwa, a refugee from the partition of Pakistan, did not try to kill Gandhi because he was attached to the land from which he came. It was surely instigated by those who spread vitriol against Gandhi, but they would not have been half as impressionable if he had not had to face his own existential problems.

Freedom At Midnight reduces the root cause of Gandhi’s assassination attempt to a rampant and quite relatable existential phenomenon: daddy issues. Pahwa’s fundamental problem with Gandhi was that he was the proverbial father of the nation. Having been disowned by his own father for fleeing a community gathering alone, he desperately seeks an opportunity to align himself with an identity. He has been stripped not only of his home, but also of his family. Killing his own father wouldn’t give him as much purpose as killing the father of all fathers.

When Pahwa is arrested after his failed assassination attempt, Gandhi’s real assassin appears. It is only his silhouette that is shown when he shoots Gandhi in the chest. Because your face or your religion are not as important to the history of the nation as your state of mind. It doesn’t matter whether he is a Hindu or a Muslim, but rather the fact that he is a lost soul in a lost nation trying to make sense of a traumatic past and a challenging future.

Richard Attenborough’s 1982 biopic Gandhi ends with the Mahatma saying his final words, “Hey Ram,” as the screen fades to black. It feels like a sudden blow to the head. But in Midnight Freedom, Advani approaches Gandhi as he takes the bullet in the chest. It unfolds at glacial speed, forcing the audience to take in this extreme attack in plain sight. Because it is not the interpretation of a British filmmaker who wants to sweep it under the rug, but that of an Indian who knows better. An Indian who realizes what Gandhi was trying to prove all his life: death, even that of the Father of the Nation, is not the death of the nation itself.

Story continues below this ad.

Ben Kingsley in and as Gandhi.

Ben Kingsley in and as Gandhi.

The final episode is prophetically titled “Hey Ram,” but Gandhi’s expression is only seen, never heard. The two words may have a new context in a new India, but Gandhi’s invocation to Lord Rama was like a short prayer for peace. He was a practicing Hindu until his last breath, but religion was only a means to a higher end. The screen doesn’t go black either, as the writers of Freedom at Midnight cannot divorce Gandhi’s sacrifice from its positive outcome.

What Gandhi could not achieve in life, he did in death. It brought together not only two religions and countries at war, but also two political ideologies. Nehru’s socialism and Patel’s iron pragmatism were at odds in a newly independent and divided India. These reflect the crossroads that India has found itself at in the last 15 years. Does it want to remain a country that celebrates unity in diversity or does it want to consolidate its identity on religious bases? But religion was never a point of contention then, any more than it is now. What is contentious is the way India asserts its identity: through slow and gradual consensus or through brute force?

Gandhi maintained that both Nehru and Patel, the favorites of the Congress and a new India, had the best interests of the nation in their respective agendas. But they are like “the two oxen yoked to the government cart”, where both will have to match their steps and not get lost. There is a reason why the day of Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination is celebrated as Martyrs’ Day. He died a martyr so that Nehru and Patel could put aside their differences and join forces in the interest of an India that could not afford further divisions.

Story continues below this ad.

It is unfortunate that it took the most extreme violent act against the most non-violent man to maintain peace and harmony in the country. But with Freedom at Midnight, Advani reminds us that more than death on this fateful day, it is the life that Gandhi lived for 78 years that shapes and defines India even today. Patel may have been appropriated now and Nehru may have been villainous, but it is clinging to Gandhi that gives all Indians a lasting identity.